On Writing & Design

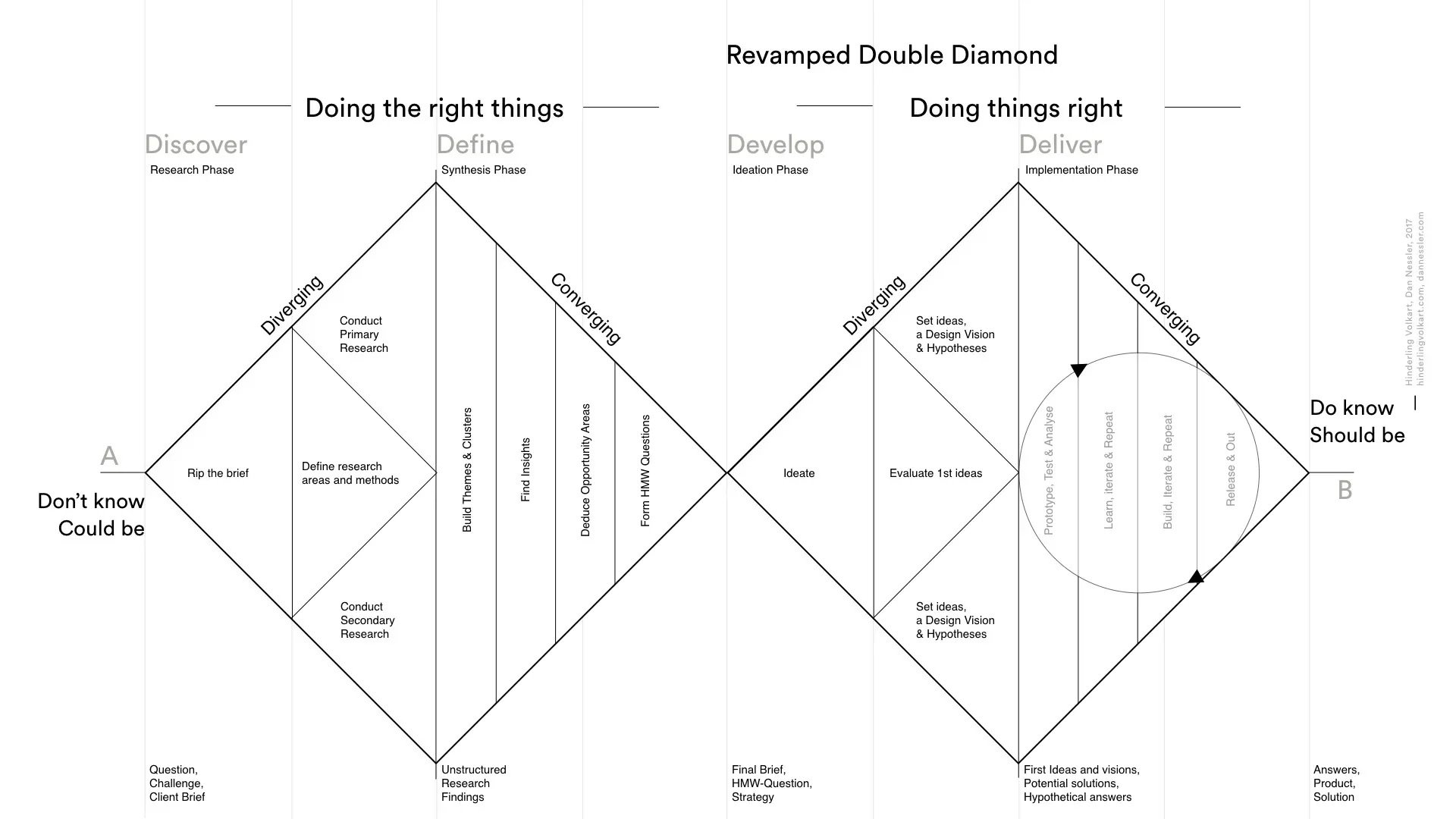

The infamous double diamond

The thing about writing and design is that they follow the same structure.

I’m not talking about structure in a technical, literary sense, but the process or format by which either discipline produces something good.

At first, you start with a problem or question—something you’re curious about or which requires deeper inquiry. You’re only trying to solve something broadly at this point, maybe even just in your mind at first. Is it worth devoting time and effort? Is it something that can sustain you for a while, or will it have an obvious, boring, or unfulfilling conclusion? What even is the central question, idea, or theme? And how do you frame it? Because your framing will give you wildly different results. And maybe it’s not not even a question at first; it’s a feeling, a desired feeling, a desire to know more, a pull to explore. But eventually, you get to a question — What if… How might we… Why do I… How did she… Is there another way to…

In these questions, you start to formulate the essence and presence of empathy not only in your work but in your everyday life (how can they be separate anyway?). You get to inspect the world more carefully through your own eyes and, eventually, through learning and gathering more about the human condition, you get to see it through the eyes of others, as well. In the words of Ray Bradbury in Zen in the Art of Writing, “Isn’t that what life is all about, the ability to go around back and come up inside other people’s heads to look out at the damned fool miracle and say: oh, so that’s how you see it!? Well, now, I must remember that.”

Writing is a way to understand yourself and the world around you. It’s a method to solidify your thoughts, to make clear, to articulate, or to make something tangible which otherwise would be ephemeral (more on this later, in the prototyping stage). Design is also a way to understand the wider world or ecosystem around you. How did these things, ways of being or working, beliefs, products, services, etc., come about? How can we make them better? How can we make them worse?

Of course, design is omnipresent. It’s everywhere around us; the good, the bad, the ugly. They say good design is invisible or unnoticeable, but to blend so seamlessly into the fabric of life, someone, at some point, had to notice quite a lot. Amongst many things, they figured out what wasn’t working and what couldn’t work, how humans behave naturally in specific situations, and all the various affordances, signifiers, and limitations that come with those specific situations. They had to be aware of what had come before and what might come after, either by their own hands (or by someone else’s, if they’re really good). And so, in this process of framing and reframing, of asking questions, research had to be done. What was said before on the topic? What is the consensus, if it exists? And if there isn’t one, why not? Are there analogous situations, environments, feelings, behaviors, and attitudes? All good writing and all good design must involve research. And really, what are we doing with either if not systematically investigating in order to reach new conclusions?

Then the fun really begins. We have ideas, but we get to expand them, push their limits, put pen to paper, whiteboard, sticky note, or whatever other medium is preferred. There are no constraints. They say the farther, wider, and longer you can diverge, the better, and isn’t that true? Have you ever written something while you were simultaneously trying to edit it? Secretly (or maybe not so secretly) judging and chastising yourself for how shit your work is. You want to believe you’re writing your first and final draft, all in one go (how nice would that be?). But how can you, or anyone, create something unique, profound, awe-inspiring, or even just something good, when you’re barely giving it the conditions to exist at all? Design is the same. Of course, constraints are useful, just like an editor is useful, but only at the right moment. Too early, you are scooping water out of a sinking ship with a bucket—no, a spoon. It’s a necessity to go far and wide, to think audaciously and “outside the box,” before you start drawing the box.

Jardin du Luxembourg

Why are improv activities so popular in these kinds of creative environments? Exercises like “In This World…” or “Whose Line Is It Anyway” type of scenarios purposefully introduce elements of the outrageous so we can condition our minds to see unrestrained possibilities. Why would my writing teacher instruct me to insert something random, something that didn’t happen at all, into a factual “story” about walking around my block? Why would he tell me to pen in an echo, something that would create anticipation, something that would produce suspense in an otherwise mundane accounting of a daily routine? We need to break out of our reality, the very situation that produced the world we occupy. Again, I’m going to quote Ray Bradbury: “… fantasy, and its robot child science fiction, is not escape at all. But a circling round of reality to enchant it and make it behave.” This is the power of divergence — the utter restriction of judgment leading to the boundless and effusive world of creation. And isn’t that a beautiful recalibration to think about? If we dial one back, we’re able to radically increase the other.

As promised earlier, we must prototype. If you’ve ever seen David Sedaris live, you know the intrinsic value of prototyping. He is a designer, without a doubt. He says he normally writes a story about eight times before he gets in front of an audience, where he ends up tweaking it another 40 or so more times afterwards. In a Fast Company interview, he said, “It takes you a week just to learn how to read it. But if you read it only once? That’s why all those stories in Barrel Fever [his 1994 book] seem so crude to me now.” Writing is rewriting. Designing is… redesigning? At least, iterating. And besides, without prototyping, how would we know we’ve made something worth talking about? When it comes down to it, what creator wants to make something in a vacuum that will rot forever under their eyes and the eyes of our almighty lord and savior?

But perhaps, in our ideating enthusiasm, we went haywire or waded too far into the deep end. Maybe it’s not a 600-page novel about theoretical demigorgon mating habits that the world needs, but perhaps there is an audience for a more nuanced, 250-page look at the demonic and underworldly creature ecosystem. Similarly, maybe the design project has $1,000 instead of $100,000. Who knows? In this prototyping phase, you’re thinking more about limits, within the writing or the project, and on yourself or your team. You’re thinking more about what your reader or user actually needs and wants. Constraints often produce better results.

And finally, of course, you absolutely must test and iterate. You get an editor and maybe focus groups. You release it into the wild under observable, scaled conditions. You make your tweaks and get ready for round two. As creators, it’s hard to ever fully finish a project. When is something done? When will it ever be good enough? The perfectionism trap is one I’m well acquainted with, but one that I know doesn’t serve anyone. That sentiment, “perfect is the enemy of good,” is coy and maybe a little trite, but also annoyingly true, as those phrases tend to be. It’s important to release work into the world, thoughtfully and carefully, especially if it will impact a great number of people. But you have to make sure you get things right, in both your writing and your designs. But I am a solid believer that you must create things that see the light of day.

Above all else, what establishing writing and design practices has taught me is that you must trust the process. When you write while you edit, you can’t let your imagination fully wander and take you off course. When you become wedded to an idea, without exploring others or testing them, you’ll never be on course in the first place. And what you’ve actually done when you skip steps in the process (which isn’t to say they always need to go in order!) is that you’ve signed up for some sad thought experiment or mimicry of a solution that someone else has probably already done (and expressed better). The work is the process. Please enjoy it. ☺